I’d been hearing the word “resilience” everywhere these past few months: on panels, in mission statements, in board retreats, staff meetings, and strategy decks. And I started to feel uneasy. Because while the word was being used constantly, it was often deployed like a mantra—vague, moralizing, strangely empty. Something you’re supposed to have. Something you’re supposed to be. Or, worse, I hear people equating endurance with resilience. Holding on. Pushing through. Grinding. That never sat right with me. Endurance may get you through the week, but it doesn’t teach you how to recover, adapt, or evolve. I wanted more to offer leaders and teams than “hold tight.” How do we actually build it, in ourselves, in our teams, in our organizations?

That hunger to be useful sent me searching. Strangely enough, it carried me into archaeology.

The Study

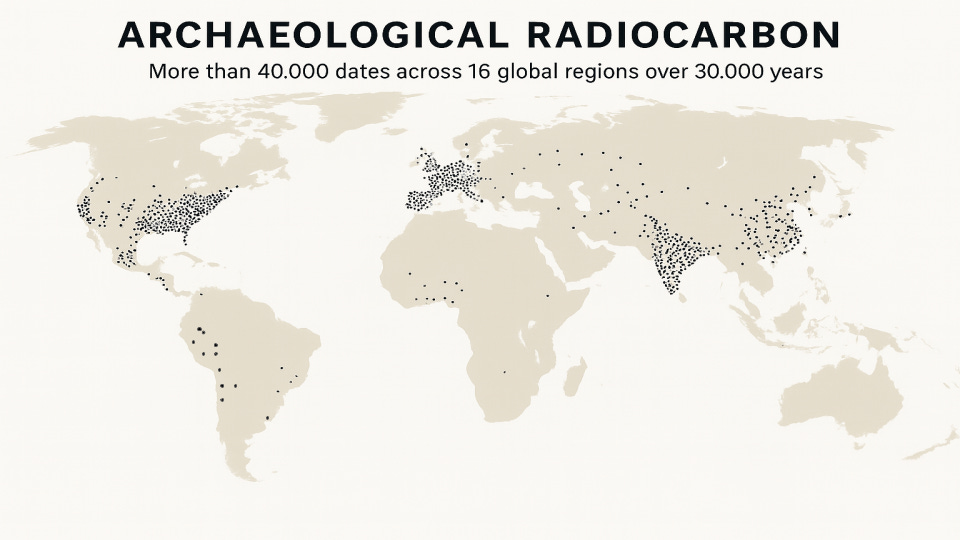

My curiosity led me to a recent study published in Nature that spanned thirty thousand years of human history. A team of researchers from across the globe analyzed 40,000 archaeological radiocarbon dates from sixteen regions. They identified 154 collapses—moments when populations shrank, fields failed, or settlements emptied out.

But the study wasn’t just about collapse. The researchers asked: How did societies recover? How quickly? How fully? The findings startled me. Societies that faced frequent disruptions recovered more fully. Collapse wasn’t only devastation. It was rehearsal. Rehearsal built reflexes. Reflexes became culture.

Four Lessons from the Long Arc of Collapse

The more I sat with the study, the more I recognized patterns that spoke to the organizations I work with today.

Lesson 01: Disturbance Builds Capacity

In the Cape of southern Africa, drought was not an occasional catastrophe but a recurring reality. Foragers learned to move with the seasons, sustaining wide networks of exchange so that when one valley failed, another could provide. What looked fragile from the outside was in fact a culture trained by repetition. Each disruption rehearsed the next.

Lesson 02: Agriculture Brought Both Risk and Resilience

In the Andean highlands, farming exposed people to famine, pests, and crop failure. But fragility also forced invention. Terraced fields carved into steep slopes, irrigation canals that stretched further each season, storage pits that carried food through lean years—risk drove adaptation, and adaptation became resilience.

Lesson 03: Collapse as Cultural Transmission

In India’s Middle Ganga Valley, collapse did not erase knowledge; it repurposed it. Rituals, political institutions, and new settlement patterns emerged from disruption. Memory became instruction. Collapse became story, and story carried survival forward.

Lesson 04: Not All Collapses Are Equal

Rigid systems broke. Flexible ones bent. In northern China, monocultures left communities brittle. When the climate shifted, their systems cracked and recovery lagged. By contrast, in Eastern North America, migration and coalition were already part of the cultural fabric. Flexibility allowed people to bend and recover more quickly.

Framing the Diagnostic

As enlightening as these learning were, the great and my big takeaway surprise was this: Resilient societies weren’t the biggest or the most resource-abundant. They weren’t the ones that managed to avoid collapse altogether. They were the ones that learned how to recover.

I used that knowledge to design a diagnostic that would allow my clients to evaluate organizational resilience. What I am offering is a mirror. A way of asking: What are we practicing, collectively? What systems help us bounce forward?

The resilience diagnostic features three key pillars. They are rooted in the archaeological lessons and combined with core principles of Adaptive Leadership, developed by Ronald Heifetz and colleagues at Harvard, which focuses on leading through change, especially in times of uncertainty, complexity, and disruption.

Organizational Resilience Diagnostic

Pillar 1: Learning, Adapting, Evolving

- Our organization reflects on past challenges to inform current decisions.

- We treat mistakes as learning moments, not blame moments.

- We have mechanisms (e.g., after-action reviews) to extract and circulate lessons.

- We evolve our strategy or operations based on what we’ve learned—not just what we planned.

Pillar 2: Innovating and Collaborating Under Pressure

- During pressure periods, we pivot rather than double down on failing plans.

- Psychological safety allows for experimentation and dissent.

- Cross-functional collaboration increases under stress.

- We have individuals or teams who model adaptive thinking and bring others with them.

Pillar 3: Shared Learning and Cultural Transmission

- When one team learns something, others can easily access it.

- We codify and carry knowledge (templates, mentorship, storytelling).

- New practices are reinforced—not just introduced and forgotten.

- Senior leaders model openness to learning and adaptation.

What Leaders Discovered

When I introduced the diagnostic to a group of thirty senior leaders from a national organization I had been supporting at their summer retreat, the shift in the room was immediate. These were people who had lived through wave after wave of disruption—political attacks, funding uncertainties, leadership changes, reductions in force—and they were hungry for a way to name and measure what resilience actually looked like in practice.

As we worked through the framework together, patterns started to emerge. Collaboration under pressure came easily to them. They knew how to rally in a crisis, how to close ranks and deliver when it mattered most. But as the discussion deepened, another reality surfaced: their learning didn’t always travel. Insights remained trapped within teams. Institutional memory leaked away with every staff departure. What they carried in strength at the level of grit and urgency, they lacked in the systems that would allow resilience to compound over time.

It was a sobering realization, but not a paralyzing one. In fact, the candor seemed to free them. People began voicing practical next steps: codifying postmortems, building rituals for storytelling, mentoring newer colleagues so that knowledge didn’t just vanish with turnover. I watched resilience move from abstraction to something tangible, something they could actually embed, measure, and improve. In that moment, it no longer felt like a buzzword. It felt like a practice they could own.

The CORE Framework

In the midst of developing the organizational diagnostic, I found myself remembering the CORE framework. It was something I had first encountered during the pandemic, when so many of us were trying to name and strengthen our own reserves. Sitting with the archaeology study, the connections came back to me with new urgency

Developed by the Center for Creative Leadership amid the COVID-19 outbreak and building on psychological research, the CORE model defines resilience as a dynamic capability that lives at the intersection of four domains:

- Mental resilience

- Emotional resilience

- Physical resilience

- Social resilience

Resilience is not a fixed trait. It is a system of habits, mindsets, and behaviors that can be practiced and strengthened. Each of these domains maps to one or two specific behaviors. I flipped those behaviors into questions—are they drivers of change, or are they reinforcing the status quo? That translation became the foundation for the Leader Resilience Diagnostic.

When It Gets Personal

After working through the organizational diagnostic, the group took the CORE diagnostic at the individual leader level. That’s when the conversation shifted from systems to selves. Sitting with thirty leaders who had already been candid about their teams, I watched them turn inward.

The honesty that followed was striking. Some admitted they had never modeled rest for their staff, confessing that they still carried the belief that grinding without pause was proof of their commitment. Others reflected on how little time they gave to gratitude or connection, acknowledging that their drive to execute often came at the expense of presence.

Because the framework was presented not as judgment but as a mirror, the responses were unguarded. No one postured or pretended to have resilience figured out. Instead, the group recognized that resilience wasn’t a trait that some people had and others didn’t. It was a system they could choose to strengthen, one they had a responsibility to practice, and one they could see clearly laddered up into the culture and performance of the organization itself. In that space of vulnerability, I saw leaders beginning to imagine what it would look like to lead differently.

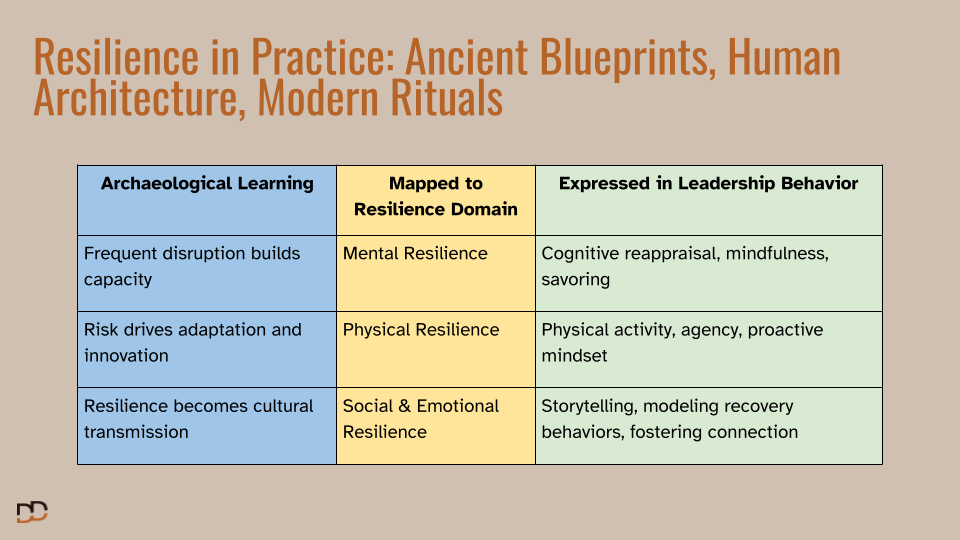

The Resilience System

After introducing both tools, I zoomed back out with the group to show how they fit together. The organizational diagnostic gave them a way to see resilience at the systems level: how their culture, structures, and practices helped or hindered their ability to bounce forward. The CORE diagnostic, by contrast, brought the lens down to the individual leader: how habits, mindsets, and daily behaviors shaped the very culture they were trying to build. Taken together, the two tools reveal resilience as a system that moves between levels. The ancient lessons provide the blueprint. The CORE framework offers the architecture. The behaviors become the rituals that bring resilience to life.

Resilience, in this light, is not a cliché. It is not sloganeering. It is a practice leaders can design, measure, and embed over time. Collapse is rehearsal for what comes next. The question isn’t whether disruption will come—it already has. The real question is: What are you rehearsing right now, and what will you pass forward?

Resilience in Practice: Ancient Blueprints, Human Architecture, Modern Rituals

An Invitation

I designed these tools to be used. If you are curious, take the leader diagnostic for yourself. Try the organizational diagnostic with your team. See what surfaces. Notice where you’re strong, and where resilience slips through the cracks.

Shortly after introducing the framework to the leaders this past summer, the chief people officer wrote to me: “Thank you for giving our team a concrete way to talk about resilience. It moved us beyond abstraction into actions we could measure and embed.” That is exactly the point. Resilience becomes real when it is practiced, not simply admired.

And if you want support—if you’d like a partner to help you introduce this framework, or to build something similar for your organization—feel free to reach out. My hope is that these tools give you a mirror and a starting point. Resilience is not just something to invoke in crisis. It’s something you can strengthen, beginning now.