Never Bark At the Big Dog. The Big Dog Is Always Right.

I told you to trust President Trump on the tariffs. I told you they would set in motion a global rush to renegotiate trade deals, and that these tariffs would not last the year.

While I explained what was going to happen, “reputable” economists lined up around the block to share their doomsday scenarios. Justin Wolfers with the Peterson Institute for International Economics called Trump’s tariff announcements

Monstrously destructive, incoherent, ill-informed … based on fabrications, imagined wrongs, discredited theories and ignorance of decades of evidence.

Lawrence Summers, former Treasury Secretary under President Clinton and deposed president of Harvard, proclaimed:

Never before has an hour of Presidential rhetoric cost so many people so much.

Paul Krugman, a Nobel Memorial Economics laureate who probably holds the world record for erroneous economic forecasting, brought out the good old Great Recession ghost from the closet. He was in good company with his fellow Nobel Memorial prize winner Simon Johnson at the highly regarded MIT Sloan School of Management. Johnson went on Swedish TV to predict the return of the Great Depression.

Speaking of Sweden, economist John Hassler was so overcome by Trump Derangement Syndrome when he heard about the tariffs that he outright lied about the formula that the Trump administration used when estimating the tariff discrepancy between the U.S. and other countries.

Topping off the anti-tariff wave was the hard-left Economic Policy Institute in Washington, DC, where the staff on a normal day loves taxes more than sharks love blood. But not this time. In a special statement the EPI declared that tariffs are good when they are used as part of central economic planning—also known as “industrial policy” or socialism—but not to encourage countries to lower their tariffs and move toward free trade.

Well, in the midst of this cacophony of single-mindedness, the Trump administration’s Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins reported that

So I think we’ll see in short order, a really positive outcome from this. We already have 50 countries that have come to the table over the last few days, over the last weeks that are willing and desperate to talk to us.

And they are all lining up to talk to the U.S. government about new trade deals.

What is so amazing—not to say pathetic—about my fellow tariffophobic economists, is that they don’t realize that Trump’s tactics is aimed at expanding free trade. He wants tariffs gone.

To understand that, though, you first have to know that other countries are putting tariffs on U.S. exports. I very much doubt that my fellow economists of all these distinguished backgrounds actually know that other countries charge tariffs on our exports. Trump wants these tariffs gone, and since simply asking to have them removed won’t work, the president is using the only language that every trade-minded government understands: reciprocal tariffs.

Even more troubling is that not a single one of those esteemed economists understands that Trump’s trade policy tactics will help cure a massive structural imbalance in the U.S. economy.

I will explain this imbalance, and how Trump’s tariff policy will help fix it. To get there, though, we have to weed through a lot of economic data—and I apologize in advance for the density of it all. However, if you stick with me to the end, you will know a lot more than economists who both get the Nobel Memorial Prize and those who hand it out. They think that understanding what you are about to learn, is simply too cumbersome.

Let us start with the obvious fact that the United States has a trade deficit with most countries. Figure 1 reports our exports as share of our imports from 71 countries for which the Bureau of Economic Analysis reports data. The red columns represent exports as being below 100 percent of imports, i.e., a trade deficit. The gray columns represent exports above 100 percent of imports.

Figure 1

We have a trade deficit with 46 of these 71 countries. If we add up all our trade for the last three years,

- We had a deficit in 2022 of $958.9 billion;

- We had a deficit in 2023 of 797.3 billion;

- We had a deficit in 2024 of 903.1 billion.

The last time we had a trade surplus was 1975. Yes, 1975.

Do any of the distinguished economists I mentioned earlier have the faintest idea of what 50 years of trade deficits do to a country’s currency, financial markets, and money supply?

Every time a foreign company buys a U.S. built product, it sells its own country’s currency and buys U.S. dollars. Those are then used to pay for what they import. By the same token, a U.S. company seeking to import something from another country sells dollars, buys the foreign currency, and makes the transaction.

All other things equal, so long as we have a balance in our foreign trade, the currency trading for trade purposes will not impact the dollar in any way. If we run a trade surplus, there will be excess demand for dollars, while a trade deficit depreciates the dollar.

The longer the trade deficit lasts, the more downward pressure is put on the dollar. See where this is going?

Any country that runs a trade deficit for 50 years will crash its currency. The only reason why that has not happened to us is that there has been a corresponding, and sometimes over-compensating inflow of U.S. dollars from foreign countries for other purposes than trade.

What purposes? Generally speaking, two:

- Foreign direct investments, where businesses and individuals in other countries acquire American companies or build their own production facilities here;

- Portfolio management, where foreign investors buy stocks and U.S. Treasury securities (to take two prominent examples).

The good news here is that the world’s interest in investing in America is far bigger than America’s interest in investing in the world. In 2024, investors from all other countries invested just over $2 trillion in the American economy, which means they bought $2 trillion by selling their local currencies, took that money to a bank in America, and then used that money to make their investments.

That same year, American investors “only” invested $856 billion in other countries. This makes for a difference of almost $1.2 trillion, which exceeds the trade deficit and therefore—all other things equal—strenghtens the dollar. This is good, of course, and it is even better to know that we have seen a net financial inflow across our borders for as long as we have had a trade deficit:

Figure 2

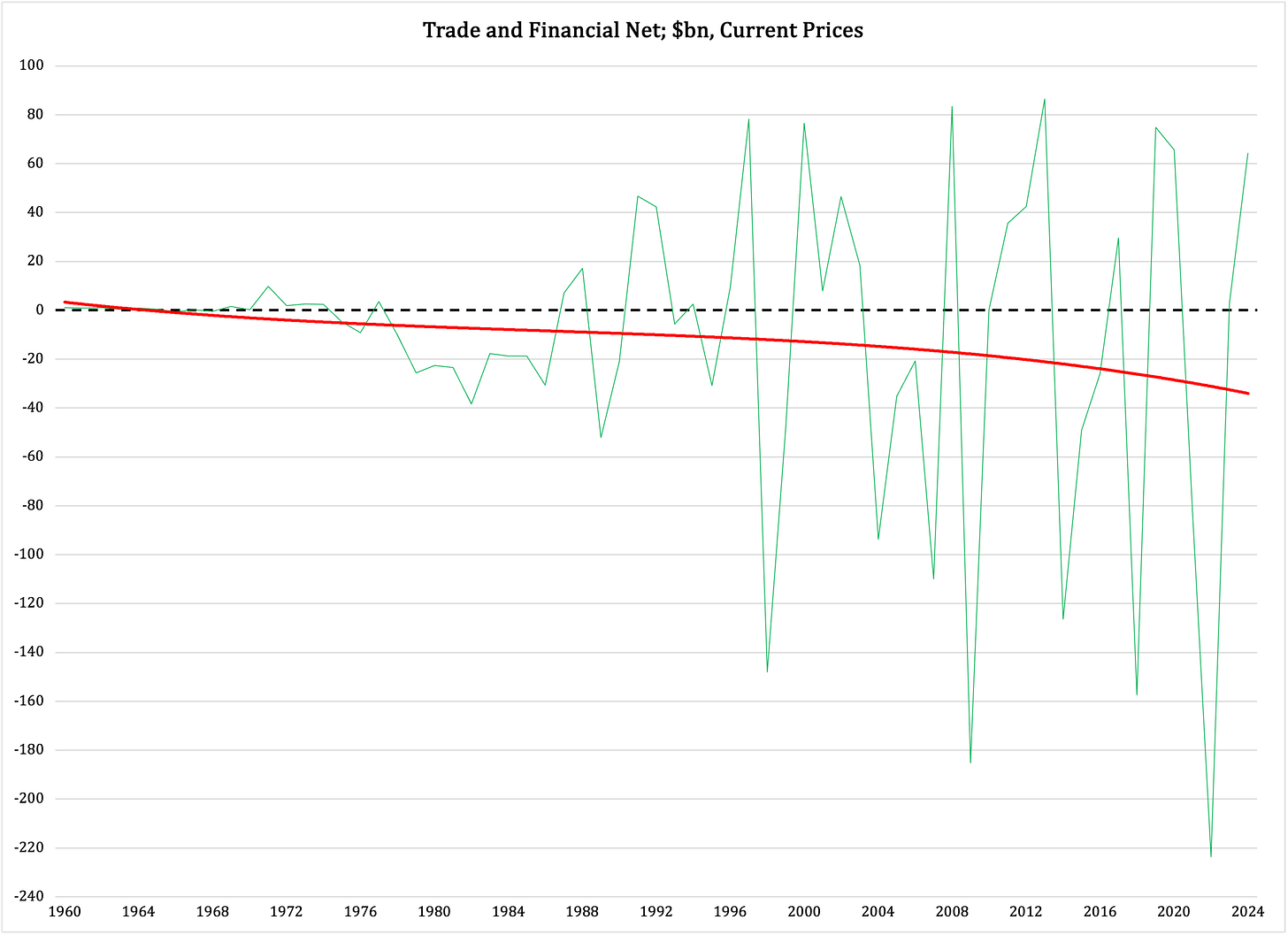

It is easy to get the impression from these two balances that they automatically cancel each other out. They don’t. As Figure 3 reports, the net between these two balances is growing increasingly negative:

Figure 3

The plain message in Figure 3 is that the U.S. economy has to work harder and harder to defend the strength of the dollar. To be clear, there are a couple of other items in the balance of (international) payments, but they are not significant enough to serve as a countervailing force to the slow decline of the trade and financial balances.

Economic theory and common sense tell us that the trend in Figure 3 is followed by a steady decline in the dollar. Yet we have not seen that: if anything, the dollar has prevailed over time, especially the 25 years that have passed since the euro was created. The common European currency was initially presented as a stronger, more conservatively managed alternative to the dollar; the best one can say about it is that it replaced the German mark on the global currency market.

All in all, the dollar remains largely unchallenged. There is a credible, growing effort from the BRICS countries, spearheaded by China, to eliminate the dollar as a global reserve currency, but so far they have not succeeded.

So how can the dollar survive despite mounting pressure from the trend in Figure 3?

The answer is uncomfortable for us Americans. Increasingly, foreign investors come here to buy up our assets—and our government’s debt. They also come here for direct investments by, e.g., building production facilities here. However, the portfolio managment motive behind our financial inflow is continuously growing more important.

Last year alone foreign investors spent $1 trillion on buying debt securities, which de facto equals Treasury bills, notes, and bonds. The share going toward portfolio management, which includes but is not limited to debt securities, has increased since the 1990s and is now the purpose behind well over half the financial inflow.

Now: so long as our equity and debt markets continue to deliver profits and safety for international investors, they will gladly come here, invest, and enjoy the profits they make. However, to guarantee the continuation of this interest from global portfolio managers, our equity markets have to continue to yield profits—which inevitably means price increases on the equity itself.

See where this is going? So long as our stock market continues to surge, and so long as our real estate prices keep going up at substantive rates, the interest in the dollar among global investors will remain high. Now that you can get 4 percent and more on Treasury securities—still an iron-clad safe investment—on top of healthy gains from Wall Street, the world is smiling in abundance when buying dollars.

There is just one problem. As I will show in a coming article, our stock market has completely lost touch with reality. The corporate values that the market produces are pure fantasies when put in a macroeconomic context. By the same token, our federal government keeps issuing new debt that it has no macroeconomic foundation for. That foundation would consist of a credible path to a balanced budget, or else we all know there is a debt crisis coming.

Long story short: our stock market must continue to rise, and our federal government must continue to sell debt, to compensate for our increasingly weaker trade-and-finance balance vs. the rest of the world. Yet the more these two markets grow investors’ earnings, the more hot air is blown into both markets.

But wait—there is more, and you knew this would loop back to the tariffs… As a result of the world charging higher tariffs on us than we charge on them, our value-producing economic activity has been increasingly stifled, especially over the past 25 years. Economic growth has slowed down markedly since the 4+ percent per year we saw in the late 1990s; under Obama, our GDP growth did not reach 3 percent a single year.

A trade deficit of $900bn per year means that we import economic value worth that much money, that we do not produce ourselves. Measured as share of GDP, our trade deficit has exploded in the last few decades:

Figure 4

The bigger the share of GDP that we import without corresponding exports, the less value we produce to motivate the profits investors make in the stock and government-debt markets.

One way or another, president Trump understands this imbalance between GDP, trade, financial flows, and U.S. asset values. His tariffs are meant to cause a rapid improvement in our trade imbalance. They are also meant to help increase GDP growth. Together, these two changes would set in motion a process to rebalance our economy and, hopefully, avoid a combined equity-debt crash.

I also invite you to take a look at this site- www.whatfinger.com

No comments:

Post a Comment