In the fall of 2010, a Chinese fishing boat was trawling off the coast of the Senkaku Islands, a territory given to Japan after World War 2 but never officially ceded by China. Upon being spotted by the Japanese Coast Guard, the trawler attempted to flee, but after being chased, it eventually rammed itself against the pursuing ship in a final act of desperation.

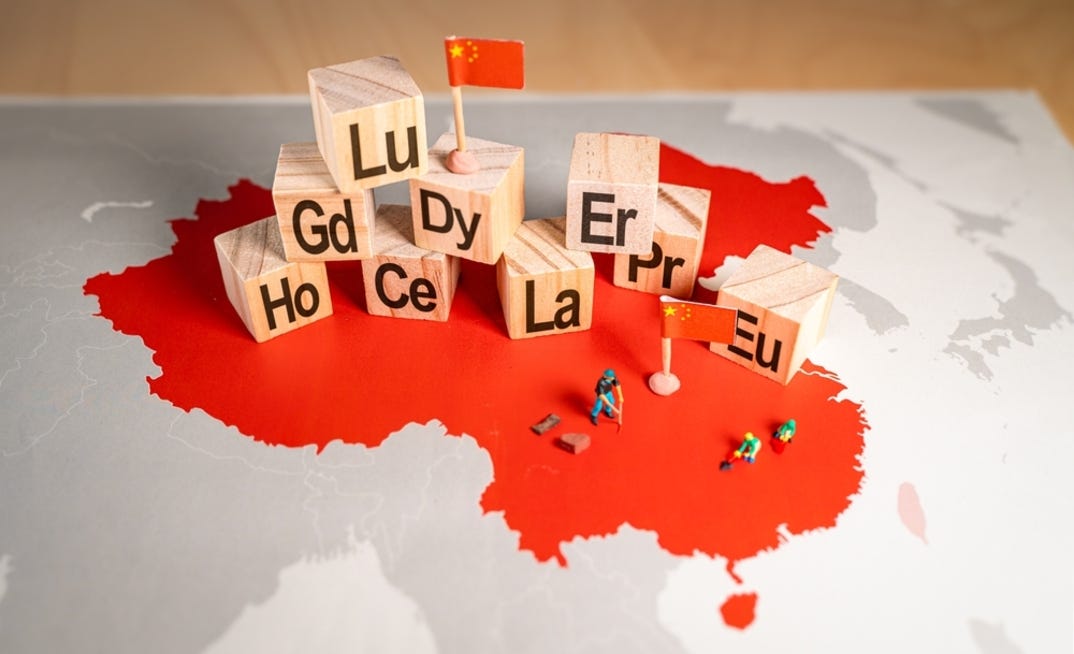

Two weeks later, in response to the fishermen’s arrest, China abruptly stopped all shipments of Rare Earth Metals to Japan, throwing their markets into turmoil. At the time, Japan sourced upwards of 90% of its rare earths from China (as did the rest of the world), as over the past few decades, China had gained near complete market dominance.

This ban, while scary at the time, ended up being relatively inconsequential to Japan, primarily because it was largely undercut by illiegal shipments out of China (a practice they have now harshly cracked down on), and due to a WTO ruling (which China publicly disagreed with, despite complying with it) which caused the ban to only last a few months. It did, however, wake Japan up to the danger of their reliance on China, causing them to diversify their mineral sources through massive investment in Australia, from which they now source close to 30% of their rare earths.

Despite the relatively small scope of China’s embargo, its potential danger at the time cannot be overstated. This group of 17 elements is the backbone of nearly all modern technology, from satellites to renewable energy to most modern weapons systems. Once refined, they are used to build magnets (necessary for wind farms and electric vehicles), catalysts (used for a wide variety of industries, but particularly useful to refine petroleum), and high-powered lasers used by the military.

Now, despite their name, these elements are not all that rare and are actually pretty abundant across the globe. They are, however, incredibly hard to extract in economically viable quantities, and even harder to refine (even this is not where the word rare comes from though, the name actually came about because, when the elements were discovered, they had never been seen before, which is a bizarre way to name new things, but I digress). Given the high upfront costs needed, it is now incredibly difficult to compete with China, which has a very well-established industry, near complete market dominance, and has been known to undercut other companies by cutting their own prices (making it impossible for new companies to compete).

Given the immense importance of these supply chains, how did we get here?

In 1980, following the short-lived rule of Mao’s successor Hua Guofeng, Deng Xiaoping emerged as the de facto leader in China, filling both the party and state apparatuses with loyalists, and maintaining his position as the vice chairman of the Chinese Communist Party. Amongst other divergences from Mao, his economy was opened to international markets, and allowed to be driven more by market forces, with more emphasis on centralized control rather than central planning. This era of Chinese history is thus marked with great economic expansion, and the birth of China as we see it today – as a manufacturing superpower.

Among these expansions was the birth of China’s rare earths industry. Blessed with somewhere around 30- 40% of the world’s known rare earth deposits (the most of any single country), China was uniquely poised to take over this market, but was far behind in the industrialization needed to take advantage of these reserves. In the decades following Deng’s ascension, three key factors allowed China to emerge as the sole superpower of rare earths.

The first is relatively simple, and the same reason why China was able to take over so much of global manufacturing within this same time period. Due to their low labor costs and relative lack of environmental standards, the costs of doing business in China were immediately much lower than anywhere else around the globe. That second part is key for rare earths – their extraction is absolutely horrible for the environment, which is a big reason why globally it takes on average 16 years to open a new mine. China’s lax regulation of environmental standards allows companies to dump waste products into the Yellow River, generate upwards of 10 million tons of wastewater a year (which is subsequently discharged without being treated, contaminating agricultural and potable water), and dump radioactive material. From 1990 to 1997, the cancer mortality rate in Bayan Obo (a rare earths mining district in Inner Mongolia) went up 50%, and the three leading causes of death were cancer, poisoning, and child mortality. Despite the human costs, however, the disregard for environmental consequences allowed China to skyrocket its production and attract investors from all over the world.

Baogang Tailings Dam in Inner Mongolia.

China then put its central planning to work, recognizing that rare earths were of vital importance to the global economy, and heavily subsidized its domestic industry, pouring money into it, and giving a 17% tax rebate for exporters. This heavy subsidization was accompanied by pouring money into R&D, pushing China forward in terms of extraction and refining technology, which was coupled with weak IPR enforcement, allowing the new technologies to proliferate amongst Chinese companies. These practices gave China a first mover advantage in rare earths processing and refining, eventually giving them the complete market dominance we see today.

The last part of China’s rare earths policy laid the foundation for the retaliatory export controls we are now seeing. Once China gained control over the market, it became very protectionist, distorting the global supply of minerals and limiting international cooperation. Whereas before, they had incentivized international cooperation and investment (particularly with Japan and the US) to facilitate the inward flow of technology and research, they now began to restrict it to limit the outward flow of their technology and research, having gained primacy.

Simultaneously, in the 90s and 2000s, China began to set lower and lower export quotas for rare earths, going from 65,000 tons in 2005 and just 30,000 by 2010. See, by this point, China was mining close to 100% of all rare earths globally, no country could compete, so by lowering the global supply, while keeping their domestic supply high, they made critical metals much cheaper for their own companies. This move allowed China to effectively vertically integrate the entire supply chain. It was now much cheaper to just buy the refined and finished products from China as well, where the cost was substantially lower. Though they would later abolish these export quotas (after the WTO ruled they violated free trade), this, however, only helped China, as it flooded the market, undercutting most other distributors of rare earths. Unsurprisingly, within this time, the two American companies capable of mining and refining rare earths, Magnequench and Molycorp, went out of business (the former was bankrupted by the supply squeeze and bought by Chinese firms, and the latter was undercut by the supply increase and crushed by debt).

In the following years, other countries have been able to regain a bit of a foothold in the actual mining process, and as of 2023, China mined around 70% of the world’s rare earths.

The damage, however, had already been done. China now controls somewhere between 85-90% of all heavy magnet production (by far the most used and profitable application of rare earths), and produces close to 100% of all heavy rare earths. Despite the fact that mines are opening up around the world, they all still send their rare earths to China to be refined and turned into usable products.

Now, this next section was supposed to be a prediction, saying that the past few decades of increasing market manipulation and retaliatory export controls meant our current tariff debacle would have the hidden unintended consequence of more expansive export controls. Unfortunately, it seems Xi Jinping (in an obvious attempt to undermine me specifically) beat me to the punch by putting bans in place this week, just a few days before I was going to publish this. So instead, let’s look at the implications of the ban China has implemented.

On April 4th, in response to further tariff hikes, China placed licensing restrictions on six medium and heavy rare earths, as well as on heavy magnets. All of the elements and magnets they have placed licensing restrictions on have a wide variety of both civilian and military applications (which likely makes this restriction WTO compliant), and are produced and refined in negligible quantities outside of China. While this is not exactly a ban, it just requires companies to now get licenses to export, it is likely to function as a ban similar to those that have come before it.

Before this last week, there had been two bans put on specific rare earths. The first came in 2023, when China banned exports of graphite (not a rare earth, but still an element critical for batteries and with a wide range of both civilian and military technology) to Sweden. The ban came as Chinese investment in battery factories across Europe (Poland and Hungary specifically). Now, one of the biggest companies in Europe’s nascent battery industry, Northvolt, just so happens to be based in Sweden. This ban, similar to the one we’re seeing now, was not an official ban, but a tweak to the export licensing system. The second ban was on the US in 2023. Following Biden’s semiconductor ban, disallowing our biggest chip companies like Nvidia to sell their best semiconductors to China, they responded by cutting off global Gallium and Germanium supplies (also not rare earths), two elements key in the manufacturing of said semiconductors.

Lastly, during Trump’s first trade war in 2019, Xi Jinping visited one of China’s cutting-edge heavy metal magnet factories, in a move that was widely perceived to be a threat to cut off their global supply. While this was not followed through on, likely due to the tentative agreement reached in 2020, this time the threat was followed through on.

These instances, as well as the policy surrounding all of China’s history with rare earth mining, refining, and production, show that they know how to protect their own industries and undercut the rest of the world. At some point, it no longer makes sense for China to continue to match our tariff level, because our trade deficit means they will always hurt more from that than we will, but what they can do is cut off our ability to actually build the products we need.

To their credit, Trump and his admin appear to understand the vital interest we have in securing this supply chain in a way I don’t think other presidents have before.

To their discredit, however, the way they’re going about it is fucking insane.

Even ignoring the fact that his trade policy has begun to cut off supplies in the short run, his incorporation of them into the center of his foreign policy is terrifying.

Specifically, his threats of annexation of Canada, taking over Greenland, and conditions to Ukraine aid all seem to have the throughline of shoring up our supply chains. When it comes to Ukraine, the cards are already on the table. The deal for Ukraine aid (which now may fall through anyway) was contingent upon the US getting to extract rare earths from Ukraine. Now, there is no credible evidence (save for some Soviet reports from the 60s) that there are rare earths in Ukraine, and even less evidence that whatever deposits they have could be worth anything (remember, the elements are everywhere, it’s about finding deposits big enough to justify the exorbitant costs). Ignoring that teensy detail, however, replacing one land-grabbing power in Ukraine with another is repugnant in my eyes. I can understand the arguments for it, that we ought to “get something out of” our aid to Ukraine, and I strongly disagree with this point of view. However, I am not going to go into the whole Ukraine debate here, and think the logistical challenges are reason enough that this plan is bad.

The even more clear-cut examples of bad policy towards the end of securing our supply chain are Canada and Greenland. For Greenland, the Trump admin has very explicitly said that they want to annex our ally for its mineral deposits. While it’s true that Greenland seems to have viable deposits, large questions remain surrounding the feasibility and cost. Annexing Canada, meanwhile, exists in this nebulous gray zone of being a joke when the idea is criticized, and being a serious policy proposal. While Trump and his admin are yet to comment on it, Trudeau has openly said that he believes Trump wants Canada for its vast mineral deposits.

Now, I don’t think the US will take over these countries any time soon, but the rhetoric surrounding American expansion is incredibly dangerous. Much of this administration seems to be reliant upon this pernicious attempt to shift the Overton window on American values, pushing us further and further towards an incredibly dangerous world. We may not invade our neighbor to the north in the next four years, but what happens when the formative political years of future politicians are filled with the idea that expansion and imperialism are key to our national security?

Outside of Trump’s foreign policy delusions, however, there is some potential good news for our supply chains and security, as we do have some prospects for companies that may be able to combat Chinese market dominance. The first is Lynas, an Australia-based rare earth mining company that produces medium and heavy metals, which was the result of Japanese investment following the embargo in 2010. The second, and more promising in my mind, is MP Materials, an American company that operates the only functional rare earth mine in the US. MP, however, is not solely a mining company, and in 2022 received grants to build up factories to process and refine rare earths, and to produce NdFeB Magnets. It is now poised to produce around 1000 tons of these magnets this year, with plans to ramp up production down the line.

A couple months ago, I invested a little in both these companies, and they have weathered the tariff storm decently well.

While the market looks something like this:

My money has looked a bit more like this:

This is not to brag or show off, but to offer what is likely going to be some of the only investing advice I ever give (in addition to telling you that you should consider buying low and selling high). I believe these companies will likely increase greatly in value over the next few months and the next few years, as the West has begun to wake up to the fact that we need to decouple this industry from China. Following the export bans on the 4th, both of them jumped about 25%, and have continued to grow. They aren’t without their drawbacks, however. Lynas is likely never going to be worth all that much, as it is just a mining company, which means it’s going to be relatively stable. MP, on the other hand, is subject to the ever-changing whim of Trump. Following its initial 25% increase on day one, it has sunk a bit and is likely to sink more on Monday, now that it has stopped selling to China due to their retaliatory 125% tariff. Despite these drawbacks, I do believe that both of these have a high potential in my mind of seeing tremendous gains over the next few months and years.

No comments:

Post a Comment